Volume 1 Issue 1

Reduction in Primary Operator Radiation Dose with Radiation Absorbing Drapes (REDUCE STUDY)

Vyom Mori1, Arun Mohanty1, Aman Makhija1, Raja Ram Mantri1, J P S Sawhney1, Rajiv Passey1, Bhuwanesh Kandpal1, Jignesh Vanani1, Ashish Kumar Jain1, Dipak Katare1

1 Department of Cardiology, Sir Ganga Ram Hospital, New Delhi-110060, India.

*Corresponding author: Vyom Mori, Department of Cardiology, Sir Ganga Ram Hospital, Old Rajinger Nagar, Delhi (2022) Reduction in Primary Operator Radiation Dose with Radiation Absorbing Drapes (REDUCE STUDY)1(1)

Copyright: ©2022 Vyom Mori, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Received: 13 June 2022| Accepted :2 July 2022|Published:04th August, 2022

Keywords: RADPAD; radiation exposure; lower the better

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Radiation absorbing shields (RADPAD) have been designed with a goal of decreasing radiation exposure to the operators during catheterization procedures. We sought to investigate the impact of RADPAD on reduction in operator radiation exposure in catheterization laboratory.

Method: The shield used is commercially available RADPAD which is lead free, composed of a bismuth and barium with lead equivalency of 0.125 mm. 152 cases of diagnostic and therapeutic angiograms were allotted in 2:1 manner with or without the RADPAD. Screening time, Cine adjusted screening time (CAST), radiation dose of primary operator was measured in all procedures. The primary endpoint was to see the reduction in ratio of primary operator dose relative to CAST in those with RADPAD.

Results: Out of 152 procedures 5 were diagnostic and 147 were therapeutic angiograms. Mean CAST was 47.3 (6.7-182) in RADPAD group and 46.33 (5.82-146.45) in no RADPAD group. The PO/CAST was 0.089±0.078 in RADPAD group and 0.234±0.28 in no RADPAD, which was significantly reduced. The operator dose was also significantly reduced in RADPAD group.

Conclusion: In this study we observed 60% reduction in PO dose/CAST in RADPAD group compared to no RADPAD cohort. The absolute PO dose in RADPAD cohort was 54% less compared to no RADPAD cohort.

INTRODUCTION

Cardiac catheterization laboratory is essential for therapeutic as well as diagnostic procedures in field of cardiology. Ionizing radiation remains an integral part of this laboratory. For staff members employed in a cardiac catheterization suite, chronic exposure to low-dose radiation confers a small but stochastic risk for inducing malignant disease, skin damage, or eye problems(1,3).There is six fold increase in radiation exposure and nearly 40 % of the increased exposure is related to Cardiovascular imaging and intervention(4). Significant radiation exposure has the potential to impact the health and well-being of interventional cardiologists and diseases like Brain Tumors (5,7), Cataracts(7), Thyroid Disease(8,9), cardiovascular diseases10, are reported in various studies. Atomic energy regulatory board (AERB) has recommended Whole body (Effective dose) as 20 mSv/year averaged over 5 consecutive years. Radiation exposure has been accepted as an occupational hazard for interventional cardiologist and other health care providers (HCP) who work with X ray-based imaging in general (1). However, it is very imperative that principle of ALARA (as low as reasonably achievable) should be practiced in every lab wherever HCPs deal with hazardous radiation. The RADPAD (Worldwide Innovations & Technologies, Inc., Kansas City, Kansas) is a sterile surgical drape containing radiation protection materials (bismuth and barium), placed appropriately on the patient between the imaging beam and the primary operator. It is known to reduce scatter radiation exposure to primary operator in routine catheterisation procedures. We sought to assess the efficacy of RADPAD drapes in reducing radiation dose experienced by operators during routine catheterization procedures in our hospital.

METHODOLOGY

Study was a single centre experience of RADPAD use during catheterization procedures. This was a prospective observational study using radiation protection shield (RADPAD, Worldwide Innovations and Technologies Inc, KS, USA), which is lead free and composite of barium and bismuth. The shielding properties are certified by the manufacturer as 0.125 mm lead equivalent.

One RADPAD shield (Femoral 5300A- Y/Multipurpose 5511A-Y) was used for this study and were placed as per the standard placement instruction from the manufacturer as shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1: Figure showing appropriate placement of RADPAD during femoral/radial procedures.

All shields were used once only. All procedures were performed in a standard PHILLIPS FD20 Cath. Lab (Catheterisation laboratory), and with usual attention to good radiological practice such as careful collimation, hanging lead curtain beneath the patient table, movable leaded glass shield fixed to the ceiling. Standard personal shielding including a lead apron and protective thyroid collar were worn by the operator. The study was performed as part of a quality assurance program with a view to monitoring and reducing dose to staff in the interventional lab with no intervention done on patient, so local ethics committee approval was waived.

Study was all comers where use of RADPAD was allotted in 2:1 pattern to “with RADPAD” (Study Group) or “without RADPAD” (Control group). Radiation exposure to primary Operator (referred as primary operator dose) was measured using ALOKA PDM 127 personal dosimeter placed over left chest above the lead apron. Recorded doses were from the primary operator dosimeter for all the procedures (DOSE). Total fluoroscopy time and no of cine acquisitions were recorded for each procedure (ST). Patient and procedural details were recorded prospectively. To consider the factor of radiation exposure on account of CINE, which emits approximately 15 times (11) more radiation than fluoroscopy (non cine screening), we derived cine adjusted screening time (CAST), using average cine duration (observed to be 4 second), factor of fifteen and number of cine acquisition. The primary operator dose was then designated to CAST for relative dose exposure (Primary operator dose/CAST). The primary endpoint of the study was to see reduction in ratio of primary operator to CAST in procedures with RADPAD compared to control. The secondary objective was to see reduction in total radiation dose in the study group.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

ST (Screening time), AK (Air kerma) and PO dose/CAST are shown in mean ± standard deviation. CAST and DOSE is measured in mean with range. One-Way ANOVA Calculator, including Tukey HSD test was used to compare mean values of radiation exposure. Scatterplot analysis and linear regression slopes of dose relative to CAST was performed. A p value 0.05 was accepted as statistically significant.

RESULTS

A total of 152 procedures were part of this study. Five were coronary angiograms and 147 were therapeutic interventional procedures. The basic demographics of the study population are enumerated in Table 1.

Variables | RADPAD N=100 (%) | NO RADPAD N=52 (%) |

AGE (Years) | 55 ± 9.5 | 53 ± 8.4 |

MALE | 74 (74) | 80 (80) |

DIABETES | 35 (35) | 12 (25) |

HYPERTENSION | 28 (28) | 16 (32) |

CLINICAL PRESENTATION | ||

Acute Coronary Syndrome | 30 (30) | 10 (20) |

Stable Angina | 70 (70) | 42 (80) |

PROCEDURAL CHARECTERISTICS | ||

Single PCI | 62 (62) | 31 (60) |

Multivessel PCI | 25 (25) | 13 (25) |

Chronic total occlusion | 2 (2) | 1 (2) |

Left Main | 4 (4) | 2 (4) |

Bifuration lesions | 6 (6) | 3 (6) |

Coronary angiograms | 1 (1) | 4 (4) |

TABLE 1: Basic demographics of the study population

*PCI-Percutaneous coronary intervention.

Basic characteristics in both the population were almost similar. Most of the patients were of stable angina in both the groups. Various diagnostic and therapeutic interventional procedures done in both the groups are mentioned with most of the procedures being single vessel PCI.

The procedural data and radiation measurements are enumerated in Table 2.

Variable | RADPAD (n=100) | NO RADPAD (n=52) | p value |

Procedural data in study cohort | |||

ST (min) | 15.97±13.38 | 16.54±13.73 | |

AK (mgy) | 3924±2296 | 3711±2076 | |

CAST(Min) | 47.3 (6.7-182) | 46.33 (5.82-146.45) | 0.3 |

DOSE (mrem) | 3.679 (0.4-14.2) | 8.12 (0.8-41.9) | <0.00001 |

PO Dose/CAST (m rem/min.) | 0.089±0.078 | 0.234±0.28 | <0.00001 |

TABLE 2- Procedural data in both the study groups.

*ST- Screening time, *AK- Air Kerma, CAST- Cine adjusted screening time, *DOSE- Radiation as measured by dosimeter, *PO/CAST- Primary operator dose/Cine adjusted screening time.

Mean ST was numerically higher in control group and AK was numerically higher in study group. The CAST was higher in control group but it was not found to statistically significant (p - 0.3). The ratio of primary operator dose to CAST was significantly reduced in the study group (0.089±0.078) compared to the control group (0.234±0.28) (p < 0.00001). There was also significant reduction in the primary operator radiation dose in study group (3.67 mrem) compared to control group (8.12 mrem) (p < 0.00001). The mean patient dose in RADPAD cohort was 96.575 m rem in RADPAD cohort and 116.95 mrem in NO RADPAD cohort.

DISCUSSION

Our study has shown that with use of radiation shields (RADPAD) there was 60% reduction the ratio of primary operator to CAST and 54% reduction in the total operator dose exposure. The reduction in radiation exposure has been found to be statistically significant. Scatter plot analysis of the groups has been shown in FIGURE 2

FIGURE 2 - Scatter Plot Analysis of PO dose/CAST, suggesting radiation exposure more if RADPAD not used.

*PO- Primary operator dose, *CAST- Cine adjusted screening time

There was also 17% reduction in the patient radiation dose exposure. The reduced radiation exposure and its beneficial effects on the health care workers has not been assessed in our study. However any amount of radiation exposure is harmful with long term stochastic effects unknown in the health care workers working among radiation.

The higher reduction in radiation dose in our study was due to use of dosimeter at chest level because that’s the maximum exposed part to radiation. Besides this RADPAD also prevents the relative radiation exposure at chest level compared to other body parts (12). In RECAP trial, use of RADPAD in catheterization laboratory lead to 20% reduction in relative dose exposure compared to NO RADPAD group and 44% reduction compared to SHAMPAD group (13). Use of drapes in CRT (Cardiac resynchronization therapy) has lead to 65% reduction in dose exposure and hand level and 40% reduction at eye level (14). RADPAD use during coronary angiography lead to 59% reduction in relative radiation exposure to the primary operator even during angiography (15). In an Indian study of 65 patients the drape reduced the radiation exposure to the operator by 39%.16 The study also concluded that maximum radiation is in left anterior oblique projection (16). Our study has shown the primary operator dose reduction of similar magnitude. Usually in diagnostic angiograms the radiation dose is 2-3 mSV but during complex PCI like bifurcations, CTO (Chronic total occlusion) or multivessel disease the exposure rises to as much as 10-15 mSV. The interventional cardiologists have an adjusted odds ratio of 4.5 for cancer, 9 for cataract, 1.7 for hypertension and 1.9 for hypercholesterolemia due to long hours of radiation exposure (17). Our study also measured the radiation dose exposure at patient level, which was found to be reduced by 17% in study group compared to control. Thus on addition to traditional radiation protection devices it becomes amenable to use this drapes. The goal should be to achieve as low as possible radiation exposure to the operator and prevent long term occurring occupational hazards.

There are three limitations of our study. One is our study is prospective observational study but however we tried to balance the baseline charecteristics between both groups. Second is we measured operator dose exposure only at the chest level rather than measuring at other body parts. Third is its limited experience single centre study.

CONCLUSION

The study showed the use of RADPAD leads to significant reduction in radiation exposure to the primary operator. Thus, with use of drapes the goal of ALARA can be achieved. How its going to effect the long-term consequences of radiation in health care workers is yet not determined. Hence whenever possible for those working long hours amongst radiation use of sterile drapes for preventing the exposure should be considered.

REFERENCES

- Venneri L, Rossi F, Botto N, Andreassi MG, Salcone N, et al. (2009) Cancer risk from professional exposure in staff working in cardiac catheterization laboratory: insights from the National Research Council's Biological Effects of Ionizing Radiation VII Report. Am Heart J.;157(1):118-124.

- Koenig TR, Wolff D, Mettler FA, Wagner LK. (2001) Skin injuries from fluoroscopically guided procedures: part 1, characteristics of radiation injury. AJR Am J Roentgenol.;177(1):3-11.

- Vano E, Gonzalez L, Fernández JM, Haskal ZJ. (2008) Eye lens exposure to radiation in interventional suites: caution is warranted. Radiology;248(3):945-953.

- Vañó E, González L, Guibelalde E, Fernández JM, Ten JI.(1998) Radiation exposure to medical staff in interventional and cardiac radiology. Br J Radiol.;71(849):954-960.

- Finkelstein MM. (1998) Is brain cancer an occupational disease of cardiologists? Can J Cardiol.;14(11):1385-1388.

- Hardell L, Mild KH, Påhlson A, Hallquist A.(2001) Ionizing radiation, cellular telephones and the risk for brain tumours. Eur J Cancer Prev;10(6):523-529.

- Jacob S, Boveda S, Bar O, Brézin A, Maccia C, et al.(2013) Interventional cardiologists and risk of radiation-induced cataract: results of a French multicenter observational study. Int J Cardiol.;167(5):1843-1847.

- Ron E, Brenner A.(2010) Non-malignant thyroid diseases after a wide range of radiation exposures. Radiat Res;174(6):877-888.

- Schneider AB, Ron E, Lubin J, Stovall M, Gierlowski TC.(1993) Dose-response relationships for radiation-induced thyroid cancer and thyroid nodules: evidence for the prolonged effects of radiation on the thyroid. J Clin Endocrinol Metab.;77(2):362-369.

- Sylvester CB, Abe JI, Patel ZS, Grande-Allen KJ.(2018) Radiation-Induced Cardiovascular Disease: Mechanisms and Importance of Linear Energy Transfer. Front Cardiovasc Med.;5:5.

- Shah B, Mai X, Tummala L, Kliger C, Bangalore S, et al.(2014) Effectiveness of fluorography versus cineangiography at reducing radiation exposure during diagnostic coronary angiography. Am J Cardiol.;113(7):1093-1098. (1), 118-124

- Kloeze C, Klompenhouwer EG, Brands PJ, Van Sambeek MR, Cuypers PW, et al (2014) Editor’s choice–use of disposable radiation-absorbing surgical drapes results in significant dose reduction during EVAR procedures. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg.;47:268–272.

- Vlastra W, Delewi R, Sjauw KD, Beijk MA, Claessen BE, et al.(2017) Efficacy of the RADPAD Protection Drape in Reducing Operators' Radiation Exposure in the Catheterization Laboratory: A Sham-Controlled Randomized Trial. Circ Cardiovasc Interv;10(11):e006058.

- Jones MA, Cocker M, Khiani R, Foley P, Qureshi N,et al (2014) The benefits of using a bismuth-containing, radiation-absorbing drape in cardiac resynchronization implant procedures. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol.;37(7):828-833.

- Kherad B, Jerichow T, Blaschke F, Noutsias M, Pieske B, et al (2018) Efficacy of RADPAD protective drape during coronary angiography. Herz.;43(4):310-314.

- Shah P, Khanna R, Kapoor A, Goel PK.(2018) Efficacy of RADPAD protection drape in reducing radiation exposure in the catheterization laboratory-First Indian study. Indian Heart J.;70 Suppl 3(Suppl 3):S265-S268.

- Andreassi MG, Piccaluga E, Guagliumi G, Del Greco M, Gaita F, et al(2016) Occupational Health Risks in Cardiac Catheterization Laboratory Workers. Circ Cardiovasc Interv;9(4):e003273.

The Cardiometabolic Continuum, A Practical and Early Preventive Strategy for Cardiometabolic Diseases

Ildefonzo Arocha Rodulfo1

1Clinical cardiologist, medical writer, Venezuelan Society of Cardiology, Claret Outpatient Clinic, Caracas, Venezuela

*Corresponding author: Ildefonzo Arocha Rodulfo, Clinical cardiologist, medical writer, Venezuelan Society of Cardiology, Claret Outpatient Clinic, Caracas, Venezuela

Citation: Ildefonzo Arocha Rodulfo (2022) The Cardiometabolic Continuum, A Practical and Early Preventive Strategy for Cardiometabolic Diseases1(1).

Copyright: © 2022 Ildefonzo Arocha Rodulfo, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Received:20 October 2022| Accepted :19 November 2022|Published: November 2022

Keywords: atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, cardiometabolic continuum, obesity, type 2 diabetes, physical inactivity, sarcopenia

Abstract

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ACVD) is the major adverse outcome in the evolution of several metabolic conditions, owing to the clustering of biochemical abnormalities involved. Metabolic conditions such as obesity, impaired fasting blood glucose (IFBG) or prediabetes and type 2 diabetes mellitus have been increasing in alarming prevalence, becoming notorious contributors to the rate of morbidity and mortality due to ACVD, including arterial hypertension, turning into a serious problem of public health as a result. Other conditions such as physical inactivity with its metabolic cluster, sarcopenia, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) seem to expand the list. Moreover, obesity in childhood has been growing at an exponential rate; thus, the excess of adiposity in children and youth will translate in an excess of cardiometabolic risk in future adults. Several longitudinal studies confirm the strong association of pediatric obesity with the persistence of adult obesity and the future development of cardiometabolic conditions, such as prediabetes, diabetes, obesity, risk of arterial hypertension and ACVD. The spirit of this review is to launch an initiative to seek and treat the metabolic factors at early age and to propose the cardiometabolic continuum as a necessary and versatile strategy for preventive intervention to reduce the morbidity and mortality due to ACVD.

Introduction

Typically, until a few decades ago, most chronic noncommunicable diseases were known to respond to various etiopathogenic mechanisms, and the conjunction or overlap between them was rare. With greater epidemiological knowledge and technological advances, what was previously conceptualized as an exception is today a rule, which has its most authentic expression in cardiometabolic diseases where a metabolic alteration, related to the metabolism of lipids and/or carbohydrates, frequently leads to atherosclerosis and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ACVD), contributing to the heavy burden of morbidity and mortality from this cause (1,2).

A publication of Global Burden Disease (3) showed that metabolic risk factors (high levels of systolic blood pressure, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), fasting plasma glucose together with smoking and higher body mass index) were the most important contributors to the coronary artery disease (CAD). Poor control of metabolic risk in developing regions translated into an increase in the number of CAD-related deaths in regions with a low sociodemographic index (SDI). Furthermore, globally, the middle-aged population showed the greatest increase in the number of deaths related to CAD attributable to metabolic risk factors; this suggests that the middle-aged population was the most affected by cardiometabolic disorders in past decades. This phenomenon is more prevalent in regions with low, low-medium, and medium SDI, where lifestyle strategies as primary prevention interventions in terms of cardiometabolic diseases are required for a wide range of population; this proves that these interventions are cost- and time-effective (4). Consequently, to state that cardiovascular and metabolic prevention strategies go hand in hand to obtain more convincing benefits and with greater coverage for the general population is fully justified, especially if there is a characteristic sequence in both pathologies that allow simultaneous intervention. For this reason, the cardiometabolic continuum was created as a tool to understand the urgence for an early intervention in these conditions, especially directed to non-specialist or untrained physicians in the broad area of cardiometabolic diseases (1,2).

The spirit of this review is to launch an initiative to seek and treat the metabolic factors at early age and to propose the cardiometabolic continuum as a necessary and versatile strategy for preventive intervention to reduce the morbidity and mortality due to ACVD.

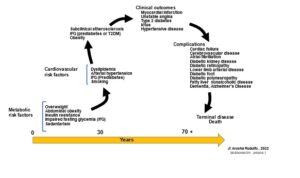

Cardiometabolic continuum, background

Most chronic non-communicable diseases develop following a kind of cycle that has been called continuous, precisely because many of them progress nonstop. The speed of this progression depends on several conditions inherent to each person: genetics, sex, age, ethnicity, environment, severity of risk factors and lifestyle habits. Although progression is unstoppable, its speed can be accelerated or delayed according to the attitude each patient faces it with; therefore, unhealthy lifestyle habits related to the cardiometabolic sphere will favor the evolution of the atherosclerosis process, with the consequent increase in the risk of a clinical event (5,6). Moreover, in this context it is understood that, despite the treatment, ACVD does not stop once started; instead, it progresses gradually, depending on variables as diverse as those already mentioned and, obviously, on the treatment, its efficacy and adherence to it. Figure 1 shows the course of the cardiometabolic continuum (CMC) where cardiovascular risk factors can coexist with various metabolic conditions that exert a special influence on the onset and progression of atherosclerosis and ACVD, leading to different cardiovascular and / or metabolic clinical scenarios (2). Modification of this cycle will translate into a greater or lesser progression of atherosclerotic damage during the lifespan.

Figure 1 :Life cycle of the cardiometabolic continuum

The cardiometabolic continuum (CMC) is conceptualized to help understand the dynamics of the pathophysiological and alterations of the clinical conditions that comprise such continuum, promote patient adherence to therapeutic strategies and avoid possible deviations in the route outlined. It is important for the primary health practitioners to understand that the pathophysiology of cardiometabolic conditions is a skein of interlocking mechanisms that lead to clinical events, one way or another; therefore, therapeutic intervention must be more energetic and comprehensive than what is expected (7,8). Since it is not a single risk factor but several with greater or lesser prominence, but interacting synergistically, thereby indicating a greater risk of ACVD events.

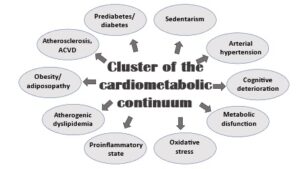

Emerging evidence suggests that microvasculature has a direct role in maintaining the function of highly metabolic organs under normal physiological conditions. Conversely, disruption of microvascular function has been implicated in disease progression of obesity-induced insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) (9,10). The vascular endothelium is in constant contact with the circulating milieu; thus, it is not surprising that obesity-driven elevations in lipids, glucose, and proinflammatory mediators induce endothelial dysfunction, vascular inflammation, and vascular remodeling in all segments of the vasculature. As cardiometabolic disease progresses, so do pathological changes in the entire vascular network, which can speed forward to exacerbate disease progression (9,10).

Consequently, this implies the existence of various alterations, metabolic or not, associated with other conditions that result in the alteration of cardiovascular homeostasis (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Complexity of the cardiometabolic continuum.

The epidemic of overweight/obesity and sedentary lifestyle in most countries has drawn attention to certain pathophysiological mechanisms, barely previously considered in the development and progression of atherosclerosis, as the main pathophysiological underpinning of CVD (4,6,7,8).

Under regular physiological conditions, insulin regulates glucose homeostasis by enhancing glucose disposal in insulin-sensitive tissues, while also regulating delivery of nutrients through its vasodilation actions on small feed arteries (10-12). Specifically, insulin-mediated production of nitric oxide (NO) from the vascular endothelium leads to increased blood flow enhancing disposal of glucose. Typically, insulin resistance is considered as a decrease in sensitivity or responsiveness to the metabolic actions of insulin, including insulin-mediated glucose disposal (11,12). However, a decreased sensitivity to the normal vascular actions of insulin, especially diminished nitric oxide production, plays an additional important role in the development of CVD in states of insulin resistance through increases in vascular stiffness (10-13).

Both overweight/obesity and sedentary lifestyle have hyperinsulinemia as a common denominator, with its consequent resistance to insulin. Such resistance begets alterations in the metabolism of carbohydrates and lipids, giving rise to a more complicated situation where the correction or modification of the initial alteration change the consequences derived from them insubstantially or not at all (14,15). Numerous and complex pathogenic pathways link obesity with the development of insulin resistance, including chronic inflammation, mitochondrial dysfunction (with the associated production of reactive oxygen species and endoplasmic reticulum stress), gut microbiota dysbiosis and adipose extracellular matrix remodelling (16-18). Insulin resistance itself plays a key role in the development of metabolic dysfunction, including hypertension, dyslipidaemia and dysglycaemia. It, furthermore, promotes weight gain related to secondary hyperinsulinaemia, with a resulting vicious cycle of worsening insulin resistance and its metabolic sequelae (16,18).

This observation makes it possible to highlight the relevance of a very important, but generally unnoticed or poorly attended, factor: time; and the reason is simple: since these modifications in metabolism are silent for many years until they become chronic and established with organic damage or clinical manifestation, untimely clinical intervention does not allow for sufficient and radical changes to be made to correct the organic consequences of such imbalances (19). This means that, with rare exceptions, management for cardiometabolic risk factors (CMRF) and ACVD is a lifelong endeavor, since drugs and changes in lifestyle only slow down the rate of progression of the cardiovascular disease, and perhaps may only reduce the risk of a cardio or cerebrovascular event (20).

It is currently accepted that each of the events in this continuum are the result of common processes participating in multiple steps through it, that may or may not be accompanied by cognitive impairment and, as the disease progresses, results in dementia and cardiac embolism or cause end-stage kidney damage and failure. In terms of prevention, the CMC is very practical, versatile, and essential in understanding a series of concatenated events that cover the transition from the appearance of CMRF, including metabolic ones, to the development of a clinical, cardiovascular, metabolic condition, or both, with the possible inclusion of another additional pathology in the course of the evolution to the outcome.

For many decades obesity has been considered as the result of a lack of discipline and higher caloric intake, in addition to the lack of necessary physical activity. This has led to certain negative attitudes to such as stigmatization of subjects with obesity and social restriction (21). Although obesity is a positive energy balance, it, in fact, comprises a complex and coordinated integration of indicators to the appetite with a chronic signaling of the energy state (22). Unfortunately, many healthcare professionals, as well as some patients, consider obesity to be a lifestyle disease, suffered by people lacking the willpower to self-regulate their food intake. But obesity is really a very complex disease with many causes, chronic and progressive, thus it should also be treated like other complex, chronic, progressive diseases; moreover, the degree of obesity is associated with complex multimorbidity, especially T2DM, in a dose–response relationship (23,24). These findings highlight the devastating impact of obesity’s association with an increasing burden of complex multimorbidity, including cardiometabolic, blood pressure, digestive, respiratory, neurological, musculoskeletal, and infectious diseases (23). This implies, mainly, that treatments must be continued on a long-term basis to avoid, delay, or minimize the complications.

The different components of energy intake and its balance regulation are factors regulated by homeostatic and non-homeostatic neural mechanisms (22,25).

Circulating hormones and vagal stimuli inform the central nervous system (CNS) about the nutritional and energy status of the entire organism. Leptin and insulin are known to be involved in the long-term regulation of energy balance, while gastrointestinal (GI) hormones and vagal afferent branches represent short-term regulatory mechanisms (26). Obesity, impaired fasting blood glucose (IFBG or prediabetes) and T2DM originally made up the group of cardiometabolic diseases; due to the accelerated growth of their prevalence, the close relationship between them with ACVD has been better understood (27). Subclinical atherosclerosis, physical inactivity, or sedentary lifestyle with all its cluster of metabolic alterations, sarcopenia, and nonalcoholic fatty liver (NAFLD) have been added to the cardiometabolic conditions. In most of these situations, the pathophysiological substrate is insulin resistance; it is not uncommon, however, for several of them to coexist, with or without arterial hypertension, which is the fatal combination to promote the progression of atherosclerosis and CVD (5,28,29). Furthermore, it must be considered that all these conditions mentioned favor the development of cognitive deterioration and dementia (30,31), an end point currently appearing at earlier ages and in a greater number of people.

Of course, any intervention, positive or negative, in CMC can modify the progression and outcomes of CVD in one way or another, as shown in Figure 1.

Cardiometabolic prevention since early age

As consequence of the description above mentioned, the prevention of cardiovascular disease must be initiated with impending metabolic risk factors such as overweight/obesity, impaired fasting glucose, or impaired glucose tolerance, sedentary behavior; these factors are usually present from the first decade of an individual’s life (19).

Extending routine systematic assessment from cardiovascular risk to cardiometabolic risk - that is, risk for developing ACVD and/or T2DM - and increasing the understanding of the basic mechanisms that regulate energy balance and metabolic risk factors, are needed to address the spread of epidemic of ACVD. Molecular and environmental conditions leading to cardiometabolic risk in early life, provide a challenge to develop effective prevention and intervention strategies to reduce the risk and modify the cardiometabolic continuum from a very early age, in order to yield earlier and greater benefits in reducing future cardiometabolic morbidity and mortality (19,32).

The main takeaway is the need for the healthcare profession to develop a

more empathetic and helpful approach to overweight/obesity and sedentarism, so patients feel encouraged to make changes in their lifestyle and gain better understanding how to go through them. It is important to note that if better lifestyle advice helps young people to avoid future cardiometabolic risk (by slowing or ceasing weight gain, losing weight, and increasing the time invested in moderate to vigorous physical activities), the potential long-term benefits to be reaped by delaying or preventing a range of clinical outcomes would be considerable (4,7,8,32).

The alarming growing in metabolic conditions presents substantial challenges to healthcare policies; it should serve as a call to improve prevention of cardiovascular disease by better targeting those at risk. At the same time, improving advice on lifestyle changes in clinical care towards sustainable better cardiometabolic health through life spam is a must (7,8,32).

Such lifestyle changes can lessen risks for several cardiometabolic diseases, including cardiovascular diseases, T2DM and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, plus potentially some cancers, as well as improve quality of life. Public health strategies have major benefits in reducing populations’ risks for cardiometabolic diseases by, for example, taxing sugar-rich beverages, more areas to sport and massive education through social media (33).

Cardiometabolic prevention strategies offer a wider chronological window, as it can be applied from an early age and, thus, modify unhealthy lifestyle habits efficiently and permanently, without requiring the investment of huge amounts of money. Furthermore, this would widen the range of healthcare specialists that can be brought onboard in the application of said strategies, including paediatricians, adolescent health specialists, primary care physicians or general physicians.

Briefly, cardiometabolic prevention precedes and complement the cardiovascular prevention across a wide spectrum of action.

Discussion

Due to the abundant documentation on the cardiometabolic issue derived from the numerous observational, epidemiological, intervention and clinical studies, the most effective strategy seems to be the early detection and treatment of the risk factors that trigger CMC as the only way to slow, stop or delay the onset and/or progression of CVD (19,34). Consequently, emphasis must be centered on primordial prevention (avoiding the appearance of risk factors) or on primary prevention (avoiding the damage caused by the risk factors present). In this regard, primary care physicians, general practitioners and doctors who are not specialists in the cardiometabolic approach are key since they receive most of the patients for the first time with some disorders of this type. Hence the importance of conceptualization as a continuum, as it is easily assimilated by the doctor and understandable to the patient as it is a vision of the problem marked by its progression over time.

The unbridled growth in the prevalence of overweight and obesity, especially in childhood and adolescence, will surely force the modification of the undergraduate and postgraduate studies in medicine, for an academic preparation in the cardiometabolic area and especially in nutrition, where it has been possible to objectify a deficiency in this knowledge in different published evaluations (35,36).

The fact that childhood obesity has gone from being a rare event to a common occurrence, with its repercussions traceable to adulthood is very alarming; so, the characterization of obesity as a matter of numbers must stop; it is essential that it be approached as a complex disease whose negative effects do not completely disappear with weight loss. In fact, obese children are five times more likely to remain obese than adults, with all attendant problems (37); moreover, many of these obese children and adolescents carry on elevated glycemic values or prediabetes resulting in earlier exposure to cardiometabolic consequences and, ultimately, long-term complications (38,39). In fact, as the prevalence rate of childhood obesity increases, a similar increase in the future burden of ACVD and T2DM is expected; therefore, policies aimed at reforming/eliminating the obesogenic environment in children and adolescents are crucial for health in future years and are an excellent long-term investment (40).

A recent cross-sectional study (41) showed that the association between body mass index (BMI) and diabetes risk in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs) is subject to substantial regional variability; a higher risk of diabetes was observed at a BMI of 23 kg/m2 or higher, with a 43% greater risk of diabetes for men and a 41% greater risk for women compared with a BMI of 18.5-22.9 kg/m2. The risk of diabetes is greater at lower BMI thresholds and at younger ages than reflected in currently used BMI cutoffs for assessing diabetes risk.

Moreover, Lawrence et al (42) , in their study to estimate changes in prevalence of type 1 and type 2 diabetes in youths 19 years or younger in the US from 2001 to 2017, found that the prevalence of type 1 diabetes was an absolute increase of 0.67 per 1000 youths (95%, CI, 0.64-0.70) and a 45.1% (95% CI, 40.0%-50.4%) relative increase over 16 years; meanwhile, the prevalence for T2DM was an absolute increase of 0.32 per 1000 youths (95% CI, 0.30-0.35) and a 95.3% (95% CI, 77.0%-115.4%) relative increase over 16 years.

More alarming is that the prevalence of T2DM in youth is increasing with a high burden of target organ damage. Follow-up data from the Treatment Options for Type 2 Diabetes in Adolescents and Youth (TODAY) (43) study show, at a mean age of 26 years (an average of 13 years after diagnosis), alarmingly high incidences of diabetes-related conditions: hypertension (68%), dyslipidaemia (52%), diabetic kidney disease (55%), and nerve disease (32%). Additionally, the incidence of retinal diseases increased from 14% to 51% in over just 7 years. While largely driven by obesity, unhealthy diets, and high levels of physical inactivity, the increasing prevalence of youth-onset (and adult) type 2 diabetes is also underpinned by socioeconomic, demographic, environmental, and genetic factors.

Regarding sedentary lifestyle, it is evident that sedentary behaviors constitute an attribute of the contemporary lifestyle and show a close relationship with various risk factors, in addition to cardiometabolic ones, such as bone health with a tendency to osteopenia, ACVD or cognitive deterioration, including increased risk of death (44-46). Indeed, high amounts of sitting time were associated with elevated likelihood of all-cause mortality and CVD in economically diverse settings, especially in low-income and lower-middle-income countries, according to a recently publication of the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology study, where a population-based cohort study included participants aged 35 to 70 years were recruited from January 1, 2003, and were followed up until August 31, 2021, in 21 high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries with a median follow-up of 11.1 years (47). Unlike physical activity programs, which involve time, transport, infrastructure, and logistics to consider, the reduction in sedentary behaviors can be achieved at a very low economic cost through simple micro-interventions, with no time limit, aimed at an increase in physical activity, modification of the sedentary habit and the implementation of activities with higher energy expenditure (48).

Health professionals, especially those dedicated to primary care or general practitioners, need to apply existing treatments in their proper dosage and as early as possible to obtain the maximum benefit and be vigilant in their adherence, as well as in strict observance of therapeutic changes in life habits. The key to success, most likely, lies in the early understanding of the pathophysiology of the cardiometabolic disorder, to be able to intervene biologically and behaviorally before a clinical outcome, which can eventually be fatal.

The clinical consequences derived from the increased cardiometabolic risk can be reflected in (1,15,30,31,49-52):

- Increased risk of CVD, as atherosclerosis is a ubiquitous condition. Generally, patients with vascular involvement in one arterial territory have atherosclerotic lesions in other arteries.

- High prevalence of T2DM and its entire clinical association with the highest risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver, cancer, and Alzheimer's dementia.

- High frequency of arterial hypertension and arrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation.

- The impact and damage on target organs such as the heart, arteries, kidney, brain, and liver.

- Deterioration in quality of life, depending on the degree of disability with lower cardiorespiratory fitness.

- High mortality, especially sudden cardiac death which, in a high percentage of cases, is the first manifestation of cardiovascular disease.

Conclusion

Evidence has shown, without a doubt, that strict compliance with treatment (pharmacological and therapeutic changes in lifestyle, especially heart-healthy diet, and daily physical activity routine), reflected in excellent metabolic control (blood glucose, A1c, LDL-C and triglycerides) and blood pressure, can reduce the probability of a vascular event or progression to T2DM by more than 50%, ensuring a better quality of life (7,8). The care of cardiometabolic conditions requires the necessary facility to interact with patients in clear and understandable language, and instruct them about the benefits of existing approaches, as well as the risks of not complying with adherence to the prescribed treatment, or of following strategies and taking medications that are not duly proven, clearly warning that the objective is not only to control altered levels of blood glucose, lipids or weight, but also to prevent CVD, the final destination of these conditions when they are not treated on time and with the appropriate intensity.

Recommendations

High rates of overweight/obesity and prediabetes are found in young peoples studied and indicated the presence an increased cardiometabolic risk to develop ACVD and T2DM and associated complications. Thus, timely intervention is mandatory to identify age-appropriate strategies that address risks and to develop recommendations for routine screening of adolescents to identify those in risks. However, a more widespread public policy must be engaged in promoting healthy eating habits, more physical activity and avoid overweight and obesity no matter age or sex. The cardiometabolic continuum is an educational tool easy to apply in routine clinical practice.

References

- Mechanick JI, Farkouh ME, Newman JD, Garvey WT.(2020) Cardiometabolic-Based chronic disease, adiposity and dysglycemia drivers: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol;75(5):525‐538

- Arocha Rodulfo JI.(2021)Approach to the cardiometabolic continuum. Narrative description. Clin Investig Arterioscler. May-Jun;33(3):158-167.

- Wang W, Hu M, Liu H, Zhang X, Li H, et al. (2021) Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 suggests that metabolic risk factors are the leading drivers of the burden of ischemic heart disease. Cell Metab. Oct 5;33(10):1943-1956.e2.

- NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC)Americas Working Group. Trends in cardiometabolic risk factors in the Americas between 1980 and 2014: a pooled analysis of population-based surveys. Lancet Glob Health. 2020 Jan;8(1):e123-e133.

- Oishi Y, Manabe I.(2020)Organ System Crosstalk in Cardiometabolic Disease in the Age of Multimorbidity. Front Cardiovasc Med; 7:64.

- Xu C, Zhang P, Cao Z.(2022)Cardiovascular health, and healthy longevity in people with and without cardiometabolic disease: A prospective cohort study. EClinicalMedicine. Mar 6;45:101329.

- Visseren FLJ, Mach F, Smulders YM, Carballo D, Koskinas KC et al (2021) ESC National Cardiac Societies; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2021 ESC Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Eur Heart J. Sep 7;42(34):3227-3337.

- Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, Buroker AB, Goldberger ZD, et al. (2019) ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2019;140:e596–e646.

- Boutagy NE, Singh AK, Sessa WC.(2022) Targeting the vasculature in cardiometabolic disease. J Clin Invest. Mar 15;132(6):e148556.

- Hill MA, Yang Y, Zhang L, Sun Z, Jia G (2021 ) Insulin resistance, cardiovascular stiffening and cardiovascular disease. Metabolism. Jun;119:154766

- Adeva-Andany MM, Martínez-Rodríguez J, González-Lucán M, Fernández-Fernández C, Castro-Quintela E (2019) Insulin resistance is a cardiovascular risk factor in humans. Diabetes Metab Syndr.;13(2):1449-1455.

- Ormazabal V, Nair S, Elfeky O, Aguayo C, Salomon C (2018) Association between insulin resistance and the development of cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Diabetol.;17(1):122.

- Wu WC, Wei JN, Chen SC, Fan KC, Lin CH, et al.(2020) Progression of insulin resistance: A link between risk factors and the incidence of diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract.;161:108050.

- Reaven GM.(2011) Insulin resistance: the link between obesity and cardiovascular disease. Med Clin North Am. Sep;95(5):875-92.

- Nieto-Martínez R, González-Rivas JP, Mechanick JI.(2021)Cardiometabolic risk: New chronic care models. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. Sep 14.

- Barber TM, Kyrou I, Randeva HS, Weickert MO.(2021) Mechanisms of Insulin Resistance at the Crossroad of Obesity with Associated Metabolic Abnormalities and Cognitive Dysfunction. Int J Mol Sci. Jan 7;22(2):546.

- Lee C-H, Lui DTW, Lam KSL.(2021) Adipocyte Fatty Acid-Binding Protein, Cardiovascular Diseases and Mortality. Front. Immunol;12:589206.

- Su X, Chang D.(2020) Role of adiposopathy and physical activity in cardio-metabolic disorder diseases. Clin Chim Acta. Dec;511:243-247.

- Makover ME, Shapiro MD, Toth PP. (2022) There is urgent need to treat atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk earlier, more intensively, and with greater precision: A review of current practice and recommendations for improved effectiveness. Am J Prev Cardiol. Aug 6;12:100371.

- Ferrari R, Cimaglia P, Rapezzi C, Tavazzi L, Guardigli G (2022) Cardiovascular prevention: sometimes dreams can come true. Eur Heart J Suppl. Nov 11;24(Suppl H):H3-H7.

- Rubino F, Puhl RM, Cummings DE, Eckel RH et al.(2020) Joint international consensus statement for ending stigma of obesity. Nat Med. Apr;26(4):485-497.

- Ludwig DS, Apovian CM, Aronne LJ, Astrup A, Cantley LC et al.(2022) Competing paradigms of obesity pathogenesis: energy balance versus carbohydrate-insulin models. Eur J Clin Nutr. Sep;76(9):1209-1221.

- Kivimäki M, Strandberg T, Pentti J, Nyberg ST, Frank P, Jokela M et al.(2022)Body-mass index and risk of obesity-related complex multimorbidity: an observational multicohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol Apr 01;10(4)253-263.

- Yu HJ, Ho M, Liu X, Yang J, Chau PH et al (2022) Association of weight status and the risks of diabetes in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Int J Obes (Lond). Jun;46(6):1101-1113.

- Timper K, Brüning JC.(2017) Hypothalamic circuits regulating appetite and energy homeostasis: pathways to obesity. Dis Model Mech; 10:679-689.

- Schneeberger M, Gomis R, Claret M.(2014) Hypothalamic and brainstem neuronal circuits controlling homeostatic energy balance. J Endocrinol.;220:T25-T46.

- Henning RJ.(2021) Obesity and obesity-induced inflammatory disease contribute to atherosclerosis: a review of the pathophysiology and treatment of obesity. Am J Cardiovasc Dis. Aug 15;11(4):504-529.

- Neeland IJ, Ross R, Després JP, Matsuzawa Y, Yamashita S et al (2019) International Atherosclerosis Society; International Chair on Cardiometabolic Risk Working Group on Visceral Obesity. Visceral and ectopic fat, atherosclerosis, and cardiometabolic disease: a position statement. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. Sep;7(9):715-725.

- Powell-Wiley TM, Poirier P, Burke LE, Després JP, Gordon-Larsen P, et al(2021)American Heart Association Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; and Stroke Council. Obesity and Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. May 25;143(21):e984-e1010.

- Sharma G, Parihar A, Talaiya T, Dubey K, Porwal B et al (2020) Cognitive impairments in type 2 diabetes, risk factors and preventive strategies. J Basic Clin Physiol Pharmacol.;31(2):/j/jbcpp.2020.31.issue-2/jbcpp-2019-0105/jbcpp-2019-0105.xml.

- Song R, Xu H, Dintica CS, Pan X-Y, Qi X, et al.(2020)Associations between cardiovascular risk, structural brain changes, and cognitive decline. J Am Coll Cardiol;75(20):2525‐2534.

- Corlin L, Short MI, Vasan RS, Xanthakis V. (2020) Association of the Duration of Ideal Cardiovascular Health Through Adulthood With Cardiometabolic Outcomes and Mortality in the Framingham Offspring Study. JAMA Cardiol. May 1;5(5):549-556.

- Barragan M, Luna V, Hammons AJ, Olvera N, Greder K et al (2022)The Abriendo Caminos Research Team. Reducing Obesogenic Eating Behaviors in Hispanic Children through a Family-Based, Culturally-Tailored RCT: Abriendo Caminos. Int J Environ Res Public Health. Feb 9;19(4):1917.

- Frohlich J, Chaldakov GN, Vinciguerra M.(2021)Cardio- and Neurometabolic Adipobiology: Consequences and Implications for Therapy. Int J Mol Sci. Apr 16;22(8):4137.

- Crowley J, Ball L, Hiddink GJ.(2019)Nutrition in medical education: a systematic review. Lancet Planet Health.;3(9):e379‐e389.

- Carter C, Harnett JE, Krass I, Gelissen IC.(2022) A review of primary healthcare practitioners' views about nutrition: implications for medical education. Int J Med Educ. May 26;13:124-137.

- Olson M, Chambers M, Shaibi G.(2017) Pediatric markers of adult cardiovascular disease. Curr Pediatr Rev.; 13(4): 255–259.

- Spurr S, Bally J, Allan D, Bullin C, McNair E.(2019) Prediabetes: An emerging public health concern in adolescents. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab. Mar 1;2(2):e00060.

- Reis JP, Allen NB, Bancks MP, Carr JJ, Lewis CE et al (2018) Duration of Diabetes and Prediabetes During Adulthood and Subclinical Atherosclerosis and Cardiac Dysfunction in Middle Age: The CARDIA Study. Diabetes Care. Apr;41(4):731-738.

- Andes LJ, Cheng YJ, Rolka DB, Gregg EW (2019) Imperatore G. Prevalence of prediabetes among adolescents and young adults in the United States, 2005-2016. JAMA Pediatr.;174(2):e194498.

- Teufel F, Seiglie JA, Geldsetzer P, Theilmann M et al. (2021)Body-mass index and diabetes risk in 57 low-income and middle-income countries: a cross-sectional study of nationally representative, individual-level data in 685 616 adults. Lancet;398(10296):238-248.

- Lawrence JM, Divers J, Isom S, Saydah S et al (2021)SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study Group. Trends in prevalence of type 1 and type 2 diabetes in children and adolescents in the US, 2001-2017. JAMA. Aug 24;326(8):717-727.

- Bjornstad P, Drews KL, Caprio S, Gubitosi-Klug R, Nathan DM, Tesfaldet B, et al.( TODAY Study Group Long-Term complications in youth-onset Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2021 Jul 29;385(5):416-426.

- Arocha Rodulfo JI. (2019)Sedentary lifestyle a disease from XXI century. Clin Investig Arterioscler. Sep-Oct;31(5):233-240. English, Spanish.

- Arocha Rodulfo I.(2022) The Cardiometabolic Burden of Sedentarism and Its Implications on Health. Clin Med Res;11(4):95-101.

- Zhao R, Bu W, Chen Y, Chen X.(2020) The dose-response associations of sedentary time with chronic diseases and the risk for all-cause mortality affected by different health status: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Nutr Health Aging;24(1):63‐70.

- Li S, Lear SA, Rangarajan S, Hu B, Yin L et al.(2022) Association of sitting time with mortality and cardiovascular events in high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries. JAMA Cardiol;7(8):796-807.

- Dunstan DW, Dogra S, Carter SE, Owen N.(2021) Sit less and move more for cardiovascular health: emerging insights and opportunities. Nat Rev Cardiol;18(9):637-648.

- Oishi Y, Manabe I.(2020) Organ system crosstalk in cardiometabolic disease in the age of multimorbidity. Front Cardiovasc Med;7:64.

- Lechner K, McKenzie AL, Kränkel N, Clemens VS,Nicolai W,et al.(2020)High-Risk atherosclerosis and metabolic phenotype: the roles of ectopic adiposity, atherogenic dyslipidemia, and inflammation. Metab Syndr Relat Disord;18(4):176‐185.

- Hegazy MA, Mansour KS, Alzyat AM, Mohammad MA, Hegazy AA.(2022)Pathogenesis and Morphology of Coronary Atheromatous Plaque as an Inlet for Interpretation of Diagnostic Imaging. J Cardiovasc Dis Res;13(1):201-218.

- Hefner M, Baliga V, Amphay K, Ramos D, Hegde V.(2021)Cardiometabolic Modification of Amyloid Beta in Alzheimer’s Disease Pathology. Front. Aging Neurosci.:13:721858.

Atypical Presentation of Raynaud's Disease with Inferior Wall Infarct

Maher M Nasser 1, Muhammad Fareed Khalid2, Mahak Khadija Bhatti3

1 Clinical Professor, Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Heart Institute, Houston, Texas.

2,3 Medical Officer, Mayo Hospital, Lahore, Pakistan.

*Corresponding author: Muhammad Fareed Khalid, Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Heart Institute, Houston, Texas,USA

Citation: Muhammad Fareed Khalid (2023) Atypical Presentation of Raynaud's Disease with Inferior Wall Infarct (1).

Copyright: © 2023 Muhammad Fareed Khalid, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Received: 27 December 2022| Accepted :28 January 2023|Published: 03 February 2023

Keywords: Raynaud’s phenomenon, myocardial infarction, vasospastic angina

Abstract

Raynaud’s disease usually presents as blanching of fingers and toes. However, it can present with atypical symptoms too. Vasospastic angina has been associated with Raynaud’s disease and can result in anginal episodes. Here, we present a case of 68-year-old patient who presented with an inferior wall infarct and was also exhibiting signs of Raynaud’s disease. We also reviewed the available literature about the pathophysiology of these vasospastic changes in patients with Raynaud’s disease.

Introduction

Raynaud Phenomenon (RP) is an exaggerated and episodic vasospasm in response to various stressors such as cold temperature or emotional stress. It presents clinically as sharply demarcated color changes of the skin of the digits and carries a significant burden of pain and hand-related disability. The correlation between Vasospastic Angina and Raynaud's has been explained in several previous observations in the literature. We present a case of an atypical case of Raynaud's with an inferior wall infarct.

Case Report

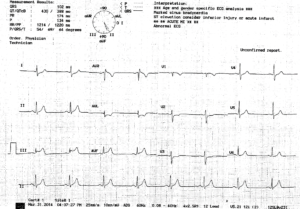

Mr. A, a 68-year-old physician, presented with a classic anginal episode manifested as central chest pain radiating to both arms for the past 1 hour. It was associated with shortness of breath and diaphoresis. EKG showed ST segment elevation in inferior leads (Figure 1). The universal diagnostic criterion of STEMI was fulfilled (1). His pain partially resolved after administering sublingual nitroglycerin (2), and subsequent EKG showed no ST elevation.

Figure 1: EKG of the patient showing ST segment elevation in leads II, III and AVF.

Over the past ten years, the patient’s extremities would show bluish discoloration and blanching when exposed to cold temperatures and while working at his office (Figure 2,3). He also has been having short episodes of chest tightness of moderate severity with no radiation to the arms that were relieved by self-induced cough.

Figure 2: Image shows the discoloration of the patient’s fingers in response to cold.

Figure 3: Image shows the blanching of patient’s fingers when exposed to colder temperatures.

On examination and during one of the episodes, the patient exhibited typical signs of Raynaud's phenomenon, including discoloration and blanching of fingers and toes. However, tibial pulses were intact, and the doppler ultrasound of the lower extremities was normal. His ANA levels showed a titer of 1:160. All other labs including troponin level, electrolytes and renal function tests were normal. Nailfold capillaroscopy was not performed at that time. His cardiovascular risk factors assessment showed no history of smoking, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, or diabetes. However, he had a strong family history of premature coronary artery disease; his father died from an acute myocardial infarction at age 61, and his three brothers died of coronary artery disease in their fifties. The patient had a remote history of H. pylori infection.

When a coronary angiogram was done, it revealed 80% occlusion of the distal Right Coronary Artery (RCA) and a 50% lesion in the mid-Left Anterior Descending artery. The RCA was stented, and patient was placed on dual anti-platelets therapy, high-intensity rosuvastatin, low-dose metoprolol, and amlodipine. On follow-up visit one month later, the patient’s condition had improves and he was no longer having any episodes of blanching of his finger and toes.

Discussion

The prevalence of Raynaud’s phenomena varies widely between populations. In the US, it is estimated that up to 200,000 people are affected. A higher prevalence among other populations, such as France, is found (3). Raynaud's phenomenon can be either a primary phenomenon or secondary to various underlying medical disorders and drug-related conditions.

Vasospastic angina, previously called Prinzmetal or variant angina, is a form of abnormal vascular response to various stimuli. Prinzmetal et al (4) initially described a clinical syndrome that manifested as rest angina associated with ST-segment elevation that promptly responded to sublingual nitrates. Since this differs from classical angina described by Heberden (effort angina associated with ST depression) (5), he referred to it as variant angina.

The correlation between vasospastic angina and Raynaud’s has been explained previously in literature (6,7). Miller et al (6) reported a high prevalence of Raynaud’s phenomenon in patients with vasospastic angina occurring at a rate of 24% in patients with variant angina as compared to 3% and 5% in controls (p-value<0.01). Hence vasospastic angina in some patients is a manifestation of a generalized vasospastic disorder and could be associated with migraine, Raynaud's phenomenon, and aspirin-induced asthma (8).

Coronary vasospasm can occur in patients with normal coronary arteries as well as in patients with atherosclerosis. However, it is still poorly understood whether coronary vasospasm can promote atherosclerotic alterations or whether the latter may predispose to spasm (9).

The patient described in our case has a typical history of Raynaud’s phenomenon diagnosed clinically, along with recurrent attacks of chest pain relieved by nitrates that were thought to be due to vasospastic angina. However, coronary angiography revealed atherosclerotic narrowing with 80% occlusion of the right coronary artery. This finding was similar to an autopsy result in one of the patients described in Prinzmetal et al paper (4), which revealed that the right coronary artery (which presumably had caused resting angina with ST elevation in inferior leads) had an 80% stenosis. This observation led to the conclusion that coronary spasm was associated with atherosclerosis. Later it was found that coronary spasms can also occur in patients with angiographically normal coronary arteries (10).

Recent experimental studies demonstrate that several endothelium-derived factors mediate vascular smooth muscle cell tone and that damaged endothelium may play a major role in the pathogenesis of vasospasm (11). Endothelial damage may occur even in the early stages of atherosclerosis. Zeiher et al (12) indicated that abnormal vasoconstriction was observed in early atherosclerotic sites in patients without variant angina using intra-coronary ultrasound. Yamagishi et al (13) reported that early stages of atherosclerosis were observed by intracoronary ultrasound at the site of spasm in patients with variant angina, even in the absence of an angiographically significant coronary disease. However, these results were challenged by a porcine model of spasm, indicating that endothelial vasodilator function was preserved at the spastic site (14); it remains to be elucidated.

It was suggested that endothelial dysfunction with decreased nitric oxide release and reduced bioavailability combined with vascular smooth muscle cell hyperreactivity might be important in developing coronary spasm. However, endothelial dysfunction alone might not be sufficient to explain vasospastic angina (15). Therefore, more studies need to be done to understand the pathophysiology associated with the vasospasm associated with Raynaud’s disease.

Conclusion:

This case highlights the importance of taking an extensive history of patient with myocardial infarction so that the root cause can be found. Raynaud’s phenomenon can present with an infarct due to atherosclerotic and vasospastic changes. This requires additional treatment of Raynaud’s disease along with MI so that further episodes can be prevented.

References

- Hegazy MA, Kamal S Mansour KS, Alzyat AS, Mohammad MA, Hegazy AA. (2022). Myocardial Infarction: Risk Factors, Pathophysiology, Classification, Assessment and Management. Cardiology Research and Reports. 4(5).

- Bosson N, Isakson B, Morgan JA, Kaji AH, Uner A et al (2019)Safety and Effectiveness of Field Nitroglycerin in Patients with Suspected ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Prehosp Emerg Care. Sep-Oct;23(5):603-611.

- Maricq HR, Carpentier PH, Weinrich MC, Keil JE, Palesch Y et al (1997) Geographic variation in the prevalence of Raynaud's phenomenon: a 5 region comparison. J Rheumatol. May;24(5):879-89. PMID: 9150076.

- Prinzmetal M, Kennamer R, Merliss R, Wada T, Bor N.(1959)Angina pectoris. I. A variant form of angina pectoris; preliminary report. Am J Med. Sep;27:375-388.

- Silverman ME. William Heberden and Some Account of a Disorder of the Breast. Clin Cardiol. 1987 Mar;10(3):211-213

- Miller D, Waters DD, Warnica W, Szlachcic J, Kreeft J (1981) Is variant angina the coronary manifestation of a generalized vasospastic disorder? N Engl J Med. Mar 26;304(13):763-766.

- Robertson D, Oates JA.(1978) Variant angina and Raynaud's phenomenon. Lancet. Feb 25;1(8061):452.

- Contreras Zuniga E, Gomez Mesa JE, Zuluaga Martinez SX, Ocampo V, Andres Urrea C.(2009)Prinzmetal's angina. Arq Bras Cardiol. Aug;93(2):e30-2.

- Ong P, Aziz A, Hansen HS, Prescott E, Athanasiadis A (2015) Structural and Functional Coronary Artery Abnormalities in Patients With Vasospastic Angina Pectoris. Circ J.;79(7):1431-1438. Epub 2015 Jun 18.

- Cheng TO, Bashour T, Kelser GA Jr, Weiss L, Bacos J.(1973) Variant angina of Prinzmetal with normal coronary arteriograms. A variant of the variant. Circulation. Mar;47(3):476-485.

- Ganz P, Alexander RW. (1985) New insights into the cellular mechanisms of vasospasm. Am J Cardiol. Sep 18;56(9):11E-15E.

- Zeiher AM, Schächlinger V, Hohnloser SH, Saurbier B, Just H. (1994) Coronary atherosclerotic wall thickening and vascular reactivity in humans. Elevated high-density lipoprotein levels ameliorate abnormal vasoconstriction in early atherosclerosis. Circulation. Jun;89(6):2525-2532.

- Yamagishi M, Miyatake K, Tamai J, Nakatani S, Koyama J et al (1994) Intravascular ultrasound detection of atherosclerosis at the site of focal vasospasm in angiographically normal or minimally narrowed coronary segments. J Am Coll Cardiol. Feb;23(2):352-357.

- Miyata K, Shimokawa H, Yamawaki T, Kunihiro I, Zhou X et al (1999) Endothelial vasodilator function is preserved at the spastic/inflammatory coronary lesions in pigs. Circulation. Sep 28;100(13):1432-1437.

- Picard F, Sayah N, Spagnoli V, Adjedj J, Varenne O. (2019) Vasospastic angina: A literature review of current evidence. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. Jan;112(1):44-55.

Disclosures

No relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

Perspectives on Coronary Artery Calcium Testing in 2023

Karley Fischer 1, Rebekah Lantz2

1MD candidate. Wright State Boonshoft School of Medicine. Dayton, OH, USA

2 DO. Premier Health Network. Dayton, OH, USA

*Corresponding author: Rebekah Lantz, DO. Premier Health Network. Dayton, OH, USA

Citation: Rebekah Lantz (2023) Perspectives on Coronary Artery Calcium Testing in 2023 1(1).

Copyright: © 2023 Rebekah Lantz, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Received: 30 January 2022| Accepted: 20 February 2023|Published: 24 February 2023

Keywords: computed tomography, non-invasive determination, coronary artery

Abstract

In regard to “Self- vs provider-referral differences for coronary artery calcium testing” by Lantz et al [1] we wish to provide updates on the use of coronary artery calcium (CAC) computed tomography (CT) testing in 2023. The test continues to be useful for noninvasive determination of future coronary risk. While it has some limitations, the benefits far outweigh the potential risks as we describe further.

Editorial:

As reported in “Self- vs provider-referral differences for coronary artery calcium testing” by Lantz et al,[1] coronary artery calcium (CAC) computerized tomography (CT) is a cost-effective noninvasive screening test that objectively quantifies burden and shows vessel distribution of coronary artery calcification.[2] Any CAC has significant implications for major adverse cardiac event (MACE) and myocardial infarction (MI).[3-4] This is due to calcification as a specific marker of subclinical atherosclerosis and surrogacy of total coronary plaque volume including less stable plaque types which may detect risk for future MI.[5] This information can be used to positively influence current and future clinical decisions. The out-of-pocket patient cost of CAC CT in most networks is approximately $100 and can be scheduled by a patient-initiated phone call or provider order. Primary care providers (PCP) can arrange the order without a cardiology referral. Detailed results within 24-48 hours provide a coronary artery Agatston score with a report of distribution. Given that coronary artery disease (CAD) is a leader in both morbidity and mortality, use of a low-cost noninvasive test that can give prognostic information and augment risk factor-based scoring should be routinely used.[6] Increased use of CAC CT identifies patients with asymptomatic CAD or a high burden of calcification, which gives opportunity for prevention and early intervention with medical therapy or invasive workup if indicated. It also identifies patients who are low risk for MACE and therefore may not need lipid lowering agents and likely have non-cardiac causes of chest pain.[7-8]

Guidelines

The 2018 American College of Cardiology (ACC) and American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines included recommendations for use of CAC CT for determining whether to initiate statin therapy in patients ages 40-75 years with intermediate (7.5-20%) atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk without diabetes mellitus and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol 70-189 mg/dL.[7] If the patient has a CAC score of 0, delaying statin therapy is reasonable. In a patient over 55 years old, a score of 1-99 indicates a potential benefit to initiate statin. In patients with a score ≥ 100 or ≥75th percentile for age, statin therapy should be prescribed, as the atherosclerosis process is well underway and risk for obstructive coronary disease increases. Statin therapy should always be initiated for baseline LDL ≥190 mg/dL and diabetes where LDL ≥70 mg/dL.[7] Guidelines have been further updated since that time and suggest utility of CAC CT beyond initiation of statin therapy for intermediate-risk patients, subgroups of patients, as well as further utility of aspirin.[9] There is additional benefit for risk stratification in patients at-risk for CAD when they present with stable or atypical symptoms.[10]

Decision-making

Clinical decision making from the CAC score has been effective in escalating invasive evaluation of stable anginal symptoms to cardiac catheterization. It was shown in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) study that there is a gradient association between score and MACE.[11] A patient with a known CAC score >400 is more likely to need cardiac catheterization and percutaneous intervention (PCI) for anginal symptoms than a patient with a CAC score of 0. This knowledge can assist the clinician in deciding who to send for invasive evaluation or provide insight on why optimization of medical therapy is not successfully reducing symptoms. Studies have reported the clinical relevance and patient benefit in having a prior documented CAC CT, even if performed years prior, in both diagnosis and treatment of a patient with accelerated or unstable angina.[10] The provider is likely to escalate therapy at a faster pace resulting in earlier intervention, which has the potential to result in PCI prior to MACE. In addition, since the vascular distribution and burden is localized and quantified with CAC CT, clinicians may even be able to correlate with early EKG changes such as T-wave inversion and R wave progression. For example, if a patient has stable angina with T-wave changes in the lateral leads, and a prior CAC CT shows high calcium burden in the left circumflex artery, this information can be used by the clinician to appropriately escalate therapy. For similar reasons, CAC CT provides additional useful data while interpreting stress tests in symptomatic patients.[12] As the clinical benefit in reducing morbidity and mortality is evident, clinicians should integrate use of CAC not only in initiating statin therapy, but also assessing patients with anginal symptoms and for risk stratification.

Limitations

Concern against regular use of CAC scoring includes a number of minor risks in testing and result outcomes. First, concern for radiation exposure has historically limited imaging to medically necessary CT scans, as radiation exposure has been associated with increased cancer risk.[13] While the risk of excessive ionizing radiation exposure is documented, the dose of radiation used to obtain a CAC CT is overall low and benefit outweighs the risk. With new CT protocols and equipment, radiation exposure has been significantly reduced without compromising imaging quality.[13] In the MESA study the mean effective dose was 1.05 milliSieverts (mSv) with a median of 0.95 mSv and a range from 0.7-10.5 mSv.[11,13] This is an equivalent exposure to a screening mammogram or 3-4 months of background radiation while living in most cities.[13] Risk of radiation induced malignancy from 1 mSv is thought to be 0.005%, suggesting the number needed to harm is 20,000. Since approximately 1 in 3 patients scanned are found to be high risk for MACE, the number needed to treat far outweighs the number needed to harm.[13]

Second, an Agatston score of 0 also does not entirely eliminate risk of MACE so there is concern regarding false reassurance with zero and low scores.[4] It should be noted that a score of 0 should not entirely alter a clinician’s differential diagnosis, as coronary artery spasm and coronary artery dissection remain possible causes of myocardial infarctions and angina in patients presenting for acute evaluation.[14-15] Alternatively, a high score does not equate with obstructive disease as the calcification could be in the arterial wall rather than intraluminal. However there remains utility to obtain CAC information in appropriate patients presenting with chest pain.

Third, there are patients with high levels of health-related anxiety where knowledge of an asymptomatic disease could lead to unnecessary and unmanageable stress. While some patients may be distressed with the discovery of coronary calcification, suggesting coronary disease, the majority of patients are able to utilize information to make healthy lifestyle changes. Positive changes include healthy lean meat and vegetable diet, ACC/AHA recommended times of exercise,[16] weight loss for overweight and obese status, smoking cessation as well as incorporating medication use for risk factor modification. Such changes ultimately improve longevity and quality of life.

Finally, cost can be a barrier to screening as the patient out-of-pocket cost is typically fixed and not currently covered by most major insurance plans. Despite cost being a limiting factor for some patients, the vast majority find the out-of-pocket cost low in comparison to insurance copays and deductibles. The test is painless, noninvasive, and convenient. While there may be question of utility regarding self-referred testing, in a study of over 2000 patients in southwest Ohio, self-referred patients had statistically similar demographics and risk factors as provider-referred patients. However self-referred patients were more reliable to self-refer with underlying peripheral vascular disease, previously abnormal cholesterol levels or prescription of an antihypertensive. They had higher CAC scores with these associations.[1]

Conclusion

In conclusion, CAC CT is useful beyond determination of statin initiation. It can define further lipid lowering augmentation as well as provide an important prediction score for future cardiac events. As the benefits of CAC CT significantly outweigh risks, patients with risk factors for coronary disease or symptoms of anginal equivalents should be screened for eligibility. Reduction of risk factors and early intervention can reduce the high morbidity and mortality associated with coronary artery disease. PCPs should include evaluation for eligibility for CAC CT at annual follow up appointments and in evaluation of acute visits for stable cardiac symptoms in patients with risk factors for CAD.

References

- Lantz R, Young S, Lubov J, Ahmed A, Markert R (2022) et al. Self- vs provider-referral differences for coronary artery calcium testing. Am Hear J Plus Cardiol Res Pract;13:100088.

- Greenland P, Blaha MJ, Budoff MJ,Erbel R, Watson KE (2018) et al. Coronary Calcium Score and Cardiovascular Risk. J Am Coll Cardiol.;72(4):434-447.

- Javaid A, Mitchell JD, Villines TC. (2021) Predictors of Coronary Artery Calcium and Long-Term Risks of Death, Myocardial Infarction, and Stroke in Young Adults. J Am Heart Assoc. Nov 16;10(22):e022513. Epub 2021 Nov 6. PMID: 34743556; PMCID: PMC8751911.

- Divakaran S, Cheezum MK, Hulten EA, Bittencourt MS, Silverman MG et al (2015)Use of cardiac CT and calcium scoring for detecting coronary plaque: implications on prognosis and patient management. Br J Radiol. Feb;88(1046):20140594.

- Mohan J, Bhatti K, Tawney A,Zeltser R(2022) Coronary Artery Calcification. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; Jan.

- Divakaran S, Cheezum MK, Hulten EA, Bittencourt M S, Silverman MG et al. (2015) Use of cardiac CT and calcium scoring for detecting coronary plaque: Implications on prognosis and patient management. Br J Radiol.;88(1046).

- Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. 2019; 139.

- Rao A, Yadu N, Pimpalwar Y, Sinha S.(2017) Utility of coronary artery calcium scores in predicting coronary atherosclerosis amongst patients with moderate risk of coronary artery disease. J Indian Coll Cardiol;7(2):55-59.

- Arnett D.K, Blumenthal R.S, Albert M.A, Buroker AB,Goldberger ZD et al. (2019) ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation, 140,e596-e646.

- Mahmood T, Shapiro MD.(2020) Coronary artery calcium testing in low intermediate risk symptomatic patients with suspected coronary artery disease: An effective gatekeeper to further testing? PLoS One;15:1-14.

- Budoff MJ, Young R, Burke G, Carr JJ, Detrano RCet al. (2018) Ten-year association of coronary artery calcium with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) events: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA). Eur Heart J.;39(25):2401b-2408b.

- Yuoness SA, Goha AM, Romsa JG, Akincioglu C, Warrington JC et al. (2015) Very high coronary artery calcium score with normal myocardial perfusion SPECT imaging is associated with a moderate incidence of severe coronary artery disease. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging;42(10):1542-1550.

- Messenger B, Li D, Nasir K, Carr JJ, Blankstein Ret al.(2016) Coronary calcium scans and radiation exposure in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging;32(3):525-529.

- Blaha MJ, Mortensen MB, Kianoush S, Maharaj RT, Achirica MC et al. (2017) Coronary Artery Calcium Scoring: Is It Time for a Change in Methodology? JACC: Cardiovasc Imaging.;10(8):923-937.

- Hussain A, Ballantyne CM, Nambi V.(2020) Zero Coronary Artery Calcium Score. Circulation;142(10):917-919.

- Piercy KL, Troiano RP, Ballard RM, et al. (2018) The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. JAMA.;320(19):2020-2028

calcification

Plagiarism Check

Olites undergoes plagiarism check through ithenticate

TRACK YOUR ARTICLE

Submit Your Article

Article Categories

Articles In Press

Volume 3, Issue 4

- Review Article

- Online Record of Version: 05 December 2023

- Ildefonzo Arocha Rodulfo

Volume 3, Issue 4

- Research Article